By The New York Times Kristin Wong June 12, 2018

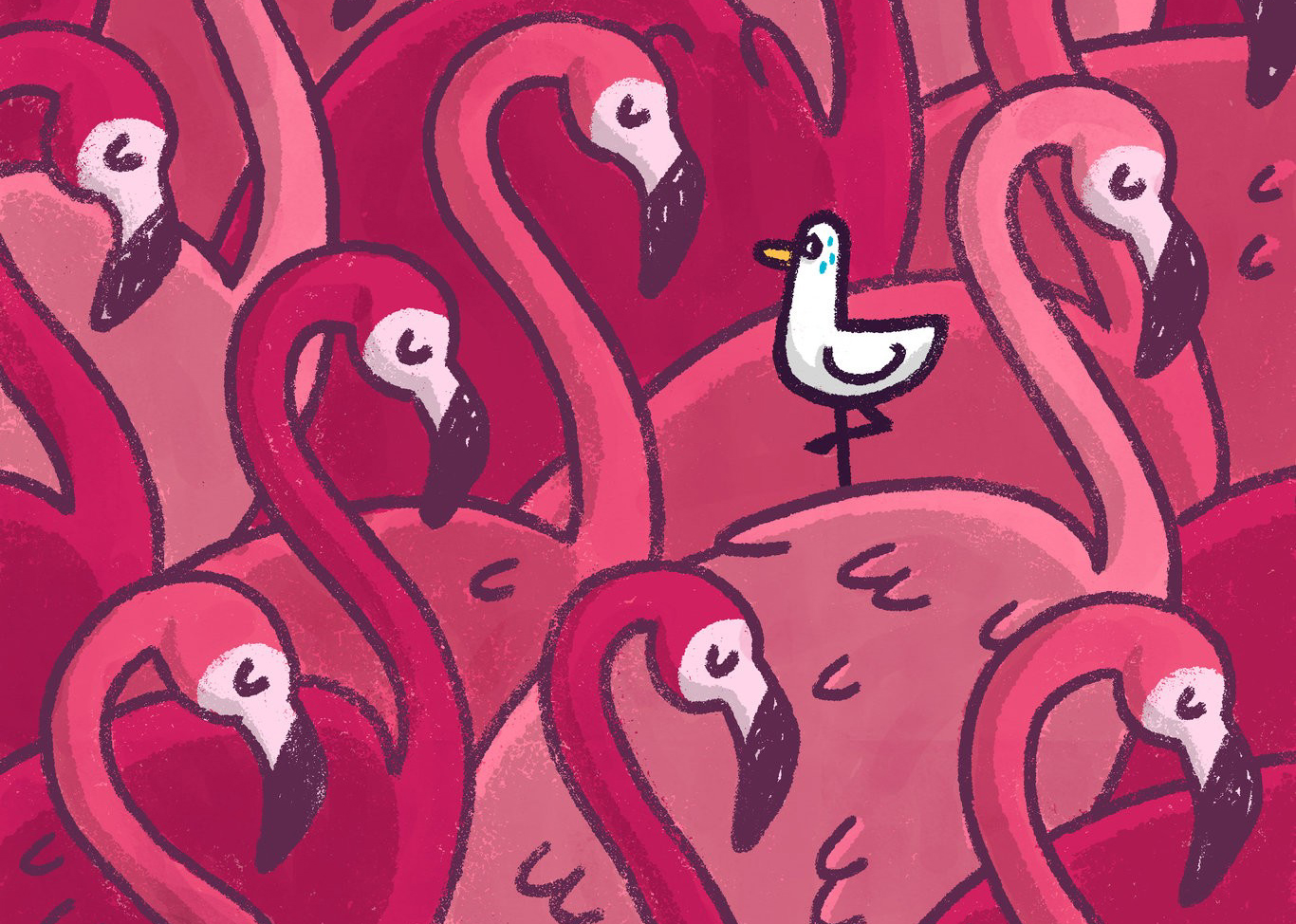

Impostor syndrome is not a unique feeling, but some researchers believe it hits minority groups harder.

Last May, I walked into a room of impeccably dressed journalists at a media event in Los Angeles. I tugged on my pilly cardigan and patted down my frizzy bangs.

When a waiter presented a tray of sliced cucumbers and prosciutto and asked, “Crudité?” I resisted the temptation to shove three of them into my mouth and instead smiled and replied, “No, thank you.” I was focused on the task at hand: pretending not to be a fraud among this crowd of professionals.

Ironically, I was at the event to interview someone about impostor syndrome.

The psychologists Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes coined the term in 1978, describing it as “internal experience of intellectual phoniness in people who believe that they are not intelligent, capable or creative despite evidence of high achievement.” In other words, it’s that sinking sense that you are a fraud in your industry, role or position, regardless of your credibility, authority or accomplishments.

This is not a unique feeling, and it hits many of us at some point in our lives. But some researchers believe it hits minority groups harder, as a lack of representation can make minorities feel like outsiders, and discrimination creates even more stress and anxiety when coupled with impostorism, according to Kevin Cokley, a professor of educational psychology and African diaspora studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

Read the full article here.